19th Century Coal Mining in Pennsylvania

|

By Mark Frederick

Though coal had been a notable source of energy in Britain and other parts of Europe in the 18th and 19th Century, it had not played as significant a role in North America. Wood, water, and animal fuel was plentiful and cheap in the United States and would be the most common source of energy for heating, mills, steam engines, forges, and other industrial activities. By 1830, that landscape began to change. Prompted by the growth of East coast cities, the higher energy content of coal and the development of coal fields near Richmond, Virginia, coal began to garner a bigger share of energy production. Growing Up in Coal Country

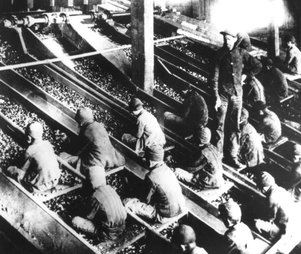

There were many strong men working in the coal industry. Except some of them weren't men, they were boys. These youngsters were called Breaker Boys. They worked in the facility where "coal was broken and sorted for market" (p. 12). These boys had to sort through "a mixture of coal, rock, slate, and other refuse" from long "iron chutes that ran from the top of the breaker to the floor" (p. 13). If one mistakenly missed an item other than coal, he was kicked or whipped by the breaker boss, who oversaw the boys and their daily routine. Sometimes "fingers were caught in conveyors and cut off" (p. 21). As was the case with so many young workers during the Gilded Age, their small frames or fingers became trapped in the massive machinery, shredded beyond all recognition.

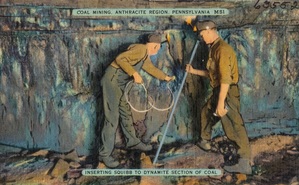

Other workers included the Nippers, who funneled fresh air deep into the mines by opening and closing the main door across the entrance. Every time the Nipper allowed someone to pass through, he would make sure the door was closed tightly behind them. This deed not only supplied oxygen for breathing, but also prevented the buildup of dangerous gases such as methane. If proper oxygen levels were not kept up, these gases had the potential to ignite flames and create deadly mine explosions. Gases could also be silent killers. To prevent carbon monoxide poisoning, a caged canary was frequently taken into the mines as a safety measure. "If the canary became panicky, the miner knew that carbon monoxide was present and further ventilation was necessary" (p. 55). Equally important were the Spraggers. These young men were responsible for the speed of the mine cars. They shoved wooden poles into the spokes acting as breaks. These individuals also frequently lost fingers or limbs as they could be wedged against the cars. Meanwhile, mule drivers had additional flexibility in the mines because they had the freedom to move about more. These workers, usually in their early teens, rode from chamber to chamber to collect full carloads of coal while also leaving empty ones behind to be refilled. During a typical day each driver and their mule would haul an impressive 100 tons of coal. All of these average workers turned mines into thriving sources of money for their employers (pp. 28-36). Many of these youthful workers dreamed of someday of becoming miners themselves, including employees known as Butties. These laborers were essentially apprentices or interns who were learning the craft of mining. Their duties included bringing the miners his tools, refilling oil lamps for light, and various other manual tasks. Other jobs included helping to stabilize shaft walls and ceilings to avoid possible collapse (pp. 55-56). If the Butty became skilled enough, he could learn to use the major tools of the trade such as "picks, shovels, bars, drills, powder, axes, and lumber." Lumber was used for stabilization, support, and creating framed entrance ways. The rest of these tools were almost always used for coal removal, whether it be by hand or by explosives (p. 54). Freedom in the Mines?

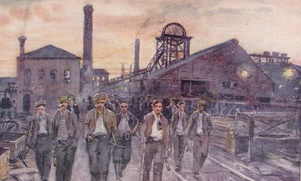

Despite all of the possible dangers involved in this job, there were also a number of individual benefits. In the darkness of the mines, miners had a type of personal independence that they could not easily have by working in a factory, mill, or railroad yard. "This freedom resulted partly from the fact that the mines contained so many miles of tunnels" (p. 57). In these mazes of coal, an individual worker had the freedom to be his own boss. This type of work shaped the character of the miner because it symbolized their rugged, rebellious, and isolated work ethic. Even while some workers were rebellious, foremen still tried to impose discipline on them, especially in the many dangerous work environments. On a daily basis, miners were exposed to explosions and the hazardous gases they released within the chambers. These same blasts could also disturb the geography of the mountain, frequently resulting in deadly cave-ins. Later on, many came down with Black Lung, a disease resulting from coal dust getting into the respiratory system. At the end of these work days, one’s own survival was often celebrated.

Coal Communities

In this atmosphere, ideas of neighborhood and family were very important. Since many bosses showed little concern for the well-being of their workers, it was important for co-workers and their loved ones to be part of a tight knit community. Mothers and women cooked, cleaned, and washed together, and watched over the children day after day. Life was not any easier for these kids in school. Teachers were strict and were not afraid to whip children to discipline them. Immigrant children were treated as stupid simply because they could not speak English as well. Others had to give up schooling because they had to fill the shoes of their father or brother who died in the mine. Children were forced to help support their families.

Life in the coal country was not all work and sweat; there was free time, too. After a tiresome day at work, most men flocked to pubs to consume alcoholic beverages. Some "stopped in for a shot of whisky or beet; which they believed was good for clearing the coal dust from their lungs" (p. 85). In these saloons, men competed to provide the best forms of entertainment like "playing cards, telling stories, reciting poems, and dancing jigs" (p. 86). In addition to their nightly carousing, the workers could also join football and baseball teams organized by different coal companies. "These Sunday games became the highlight of the week" (p. 86). There were many activities and games children could participate in. Soon big entertainment industries, including the circus and movies, arrived in the coal country. This became a problem for the coal industry because most of the young employees wanted to attend the circus or movie rather than go to work. After paydays, the younger boys would go to the local general store and candy and soda while the older men were interested in the gambling, saloons, and cock fights (pp. 89-90). Coal Conflicts

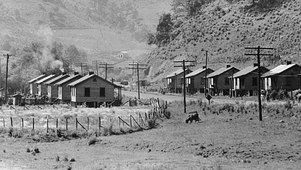

While their employers lived comfortably in large mansions in Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and Wilkes-Barre, the poorer miners and their families lived in far less comfortable homes. Usually living in structures known as "company homes," workers paid rent to their employers. Since their rent was so high, they took in boarders to make ends meet, "sometimes as many as twenty to thirty people crowded into one shack" (p. 68). These houses were not only often small and drafty, but they were also quite dangerous at times. Not only could their houses easily burn down in the case of the fire, but sometimes homes were actually constructed on top of mines—resulting in homes falling into sink wells and old mine shafts.

As "terrible conditions and unfair practices" continued in the mines, the workforce tried to strike and form unions. "The coal miners wanted shorter work days, more money, better living conditions, an end to compulsory purchases at the company store, and an end to discrimination" (pp. 106-107). Between 1842 and 1897 many protests failed in uniting the workers. Several secret societies arose from these movements, The Molly Maguires being the most famous. This group and more like them used violence, murder, and terror "to get even with the coal company." In 1897, near Hazelton Mines, a crowd of protesters were fired upon by the sheriff's deputies, killing nineteen people. Lawmen for hire such as the Pinkerton Detectives could ruthlessly strike miners down. Likewise, state militia would frequently be ordered to bring rebellion to an end. Occasionally, striking could result in successes such as wage increases, eight hour work days, and/or safer conditions. Over time, workers were replaced by machines, jobs were lost, and coal resources began to disappear. Even though many mines closed in the 20th century, the personalities and legacies of coal country remain strong aspects of the state's history. The hard work of such individuals remain models of personal strength, duty to family, and perseverance. Their story is also a legacy of the long heritage of individual triumph and industrial might. Regardless of the ups and downs in their lives, Pennsylvania miners remain an icon of the American work ethic. |

Forty years I worked with pick and drill. |