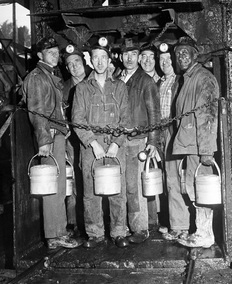

20th Century Coal Mining in Pennsylvania

|

By Shannon Simpson

As the 19th century became the 20th, the industry of coal began to change. At the start of the 20th century, the anthracite coal industry was booming in Pennsylvania and employed around 180,000 workers. In contrast to bituminous coal, anthracite is harder and gives off less smoke, making it better for burning in urban areas and the preferred fuel for heating homes throughout the northeastern United States. From 1900-1920, the coal industry brought about a wave of prosperity. Rising coal demand, during the First World War led to increased wages and working time for miners. Child labor declined, due to new legislation and their parents rising wages, however was still an issue. As the 1920’s drew to an end, the demand for coal began to decline. Long labor strikes resulted in of officials and investigation of coal mines. As one can imagine, the 1930s were not good for the industry, as workers were going through the Great Depression. As the price of coal fell, coal companies closed down their less productive mines, leaving some workers with no work while others were unaffected. This led many companies to run on rotations, allowing every employee an equal amount of hours. Other workers responded to the depression by initiating what became known as "coal bootlegging" or illegal working of closed mines. The Second World War increased the demand for coal (temporarily) but decreased the supply of workers as working-aged men were being drafted into the military. After the war, demand for coal fell drastically while output increased. This created an intense amount of financial pressure on coal companies and they began to close. Employment in the industry fell to 17,000 workers by 1961 and only 2,000 by 1974. Following the decline of the coal industry, Pennsylvania communities attempted to attract new industries to replace anthracite, with mixed amounts of success. Three successful efforts were seen by the cities of Scranton, Wilkes-Barre and Hazleton, all of whom received monetary contributions from private citizens to develop new plant sites and subsidize relocation of employers. The anthracite boom, bottomed out, in employment in 1960. Children of the time period, on average, fared much better than their parents economically. The end of the coal industry caused parents to encourage the importance of education, so the rate of high school graduation and attendance to post-secondary schools increased. |